Last year, we signed our son up for teeball. He was only out of the hospital for a few months and was still having seizures and suffering from severe ataxia and behavioral issues from the seizures and medicine, but we wanted to give him a bit of “normal”.

There were times when he would be in the field, in the “ready position”, wobbly and shaking from the ataxia, and he would have a seizure…the audible cue, his body glove slumping down and his body sagging. These seizures were short, he would spring right back up, back in position and waiting for the ball. If we tried to get him to leave, he would say no so we would monitor him and he was usually able to finish the game.

When the game was over, though, he would be so exhausted, and the exhaustion was sometimes followed by episodes of his extreme, angry behavior. We’d put him in the stroller to take him home, and he would be saying mean, hurtful things, or spitting, or hitting. We’d get him in to the house and hold him until the storm passed and he was able to calm down and take a nap.

There were good moments, too. Towards the end of the season, the coaches used a pitching machine instead the tee. Most of the kids would go up and strike out since it was obviously their first time trying to hit a moving target. But I’ve been pitching to my son for years…the tee we had was too big so we just pitched it to him and he would hit it. So he would step up to the plate, ataxic and off-balance, like a drunk stumbling down the street. He would go through the motions to get his feet set, his hands around the bat that he would lift up to his shoulder, and sway back and forth waiting for the pitch to come. When it did, his soft, fluid motion would bring the bat in perfect contact with the ball and he would crush it, and the look on his face made every other thought disappear.

It was a balancing act…trying to give him an opportunity to do something fun with other kids but managing his seizures and minimizing the behavioral issues. There was no right answer. I felt like I was a terrible parent for putting him in the situation, and I felt equally terrible on those days where we’d skip the games and he would sit inside, isolated, lonely, and just as angry and having just as many seizures.

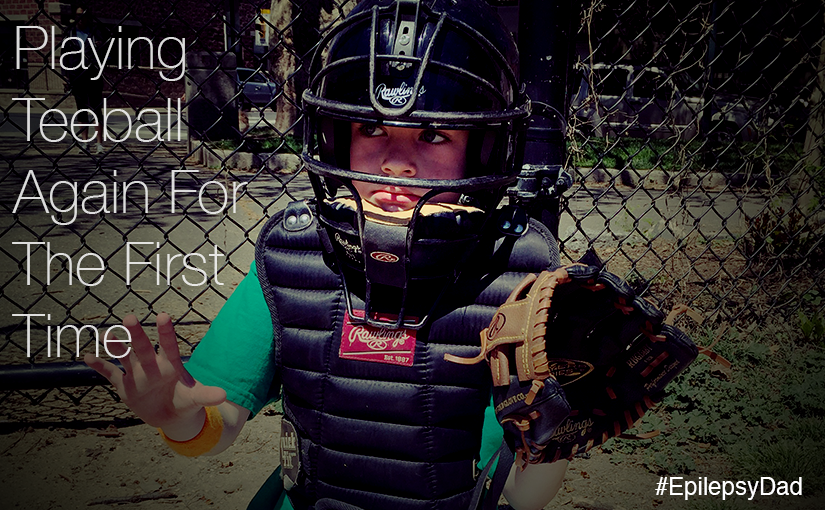

We’ve come a long way in the last year. My son is again playing teeball. His ataxia is better but still visible, but his behavior is much more under control. He’s cheering on the other batters and saying “Batter up!” and “Good job!” as the other team crossed the plate. There have not been any on-field seizures and, after our last game, he played at the park with his friends because we didn’t need to rush home because of seizures or to brace for the oncoming fatigue-induced anger.

My son doesn’t remember much about his first year of teeball, one of many holes that was caused by the seizures and the medicine. There are times when I wish I could forget last year, as well. But even though he doesn’t remember, I saw moments of joy and a sense of accomplishment as he hit the ball or ran to a base, and those are the memories that I choose to think of when I look back. If any memories from that time do come back to him, I hope that is what he remembers, too.

But if he never remembers last year, and if he only remembers his experiences this year, I’m grateful that we have this opportunity for him to play teeball again…for the first time.