I was listening to a recent episode of Adam Grant’s Work/Life podcast where he and author Susan Dominus discussed the psychology of achievement and success. There were a few quotes from the episode that stuck out to me as the parent of a child with special needs.

I think this idea that parents are burned with, which is that if their child does not succeed in some socially conventional way, that they have not done their job.

That idea used to live rent-free in my head.

I thought my job as a parent was to prepare my son for the world—and by “the world,” I meant the conventional path: grade school, high school, college, career. That was the map I followed for the first five years of his life.

Then he started having seizures. He was diagnosed with epilepsy. And still, I clung to that same definition of success. I believed I could outwork the diagnosis, push through the limitations, and keep him on the traditional track. But the more I pushed, the harder it became—on both of us.

Eventually, I realized that holding on to that version of success was causing harm. Not just to his progress, but to his spirit—and to our relationship.

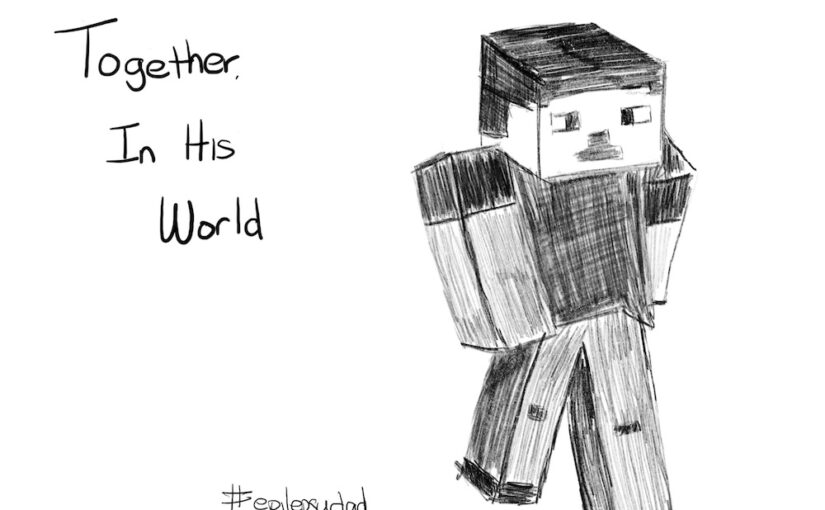

My job is to prepare my son for the world. But first, I have to meet him where he is. Not where society expects him to be. Not where I once hoped he’d be.

Right here, right now.

Is it a parent’s job to measure their child’s utility and successfulness in life?

It is a painful trap to judge our parenting by how well our kids reflect society’s idea of worth. We start to see them as mirrors of our own success or failure. We fear that they won’t measure up if they don’t fit in, if they are awkward, or if they don’t meet the normalized expectations of a traditional education, career, and life. It’s bad enough that, unless you have an extraordinary talent or athletic ability, fit unrealistic expectations of beauty, or have an idea that can make a fortune, you’re already excluded from those seen as the most valuable.

And more dangerously, we risk not seeing our children at all.

There’s all kinds of success.

Success shouldn’t be a single destination. It should be a personal journey—based on who he is, what he loves, and what he’s capable of. My job is not to chart the course, but to walk beside him, to clear the obstacles, and to remind him that his path is valid—even if it doesn’t look like anyone else’s.

That’s the shift I’ve had to make: from measuring success by milestones to celebrating presence, progress, and personhood. My son may not follow the path I once imagined, but every step he takes on his path is a triumph. And every time I choose to see him—not through the lens of expectation, but through the truth of who he is—I succeed, too.