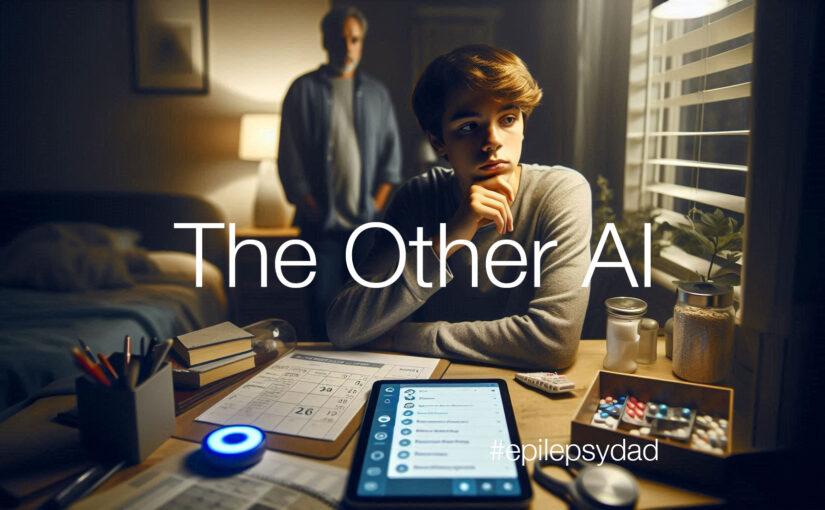

My son has been asking more frequently about living by himself. We’ll have a talk about independence and responsibility, and loosely talk about goals to help him move in that direction. But I also watch as he struggles to remember whether he had taken his medication, or put on deodorant, or pull his sheets up when he makes his bed.

As I watched him try to piece it together, I thought about the technology that I work with and whether it could help him.

I’ve been involved with computers and technology for most of my life, building products with bits and bytes of code and data. For the past ten years, I’ve worked in the evolving field of artificial intelligence (AI).

I recognized early on that AI could potentially transform my son’s life. As the technology matured, I watched it advance the state of medicine and healthcare.

Today, AI algorithms power diagnostic tools, accelerating the time to detect, identify, and treat complex medical conditions. AI is accelerating drug discovery, helping researchers identify promising treatments faster than ever before. It is also being used to examine genetic data to identify the right medication and dosage for individual patients.

AI could improve his quality of life in ways that weren’t possible only a few years ago. Pattern recognition can alert us when he misses a medication or a meal. Personal assistants can provide reminders, keep him on task, and communicate with him in a way that he understands. Self-driving cars will give him mobility and access to a wider world. AI-driven tools can assist him with complex tasks, help him communicate ideas, and give him greater autonomy and independence.

That’s the promise and the potential.

But here’s the problem. We live in a world where AI is already causing harm.

Inherent challenges with the technology, especially with generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT), result in hallucinations where the algorithm makes things up. The black-box nature of these algorithms makes them unpredictable and impossible to test fully, resulting in harmful behavior. And these algorithms are owned by corporations who control the data, usage, and output and can tune it to fit their agenda.

Beyond technology, people have been using these tools for nefarious purposes. It’s easy to create a false but believable story and share it on social media. It’s also easy to create completely believable but fake images and videos to mislead viewers. These bad actors are using the technology to push false narratives and generate mistrust and dissent in society.

My son struggles with memory and executive functioning. It impacts his ability to reason and determine whether what he is reading is fact or opinion, truth or lies. While I think society at large has lost its ability to thing critically, people like my son are especially susceptible to these false narratives and the harm they can cause.

So while I’m building the future with AI, I’m also guarding the present for my son. I want him to have access to all the promise this technology offers — the support, the independence, the chance to live on his own — without falling victim to its dangers. I have to be his guide, his filter, and his advocate.

Because while AI might one day help him remember his medication or build a career, it won’t teach him who to trust, what’s real, or what truly matters. It’s my job to walk beside him, protect him, and help him make sense of a world that’s changing faster than any of us can keep up with.