A few weeks ago, my son’s science teacher e-mailed a video to the parents of his class. In the video, the students were blowing through straws to move a paper ball around the table to show the power of air. The camera panned across the room showing groups of kids performing their experiment.

I watched the video, eager to see my son. When his table finally came in to view, I could see his classmates doing the experiment. But my son was off his chair, standing and facing the wrong direction. The camera caught his aide helping him turn around and back into his seat before it moved on to the next table. I didn’t see it, but I am sure he said he was sorry to his aide and then tried again. Because that’s what he always does.

My son is always surrounded by people who are there to help him. Whether it’s because of ADHD or side effects of his medication, he struggles to regulate his attention and emotions. The excitement of his crowded classroom is too much. Being left alone is too much. Trying to sequence events or remember the steps to a math problem is too much. Everything we ask him to do is a slippery slope down a path where someone has to be there to catch him.

The worst part is that he seems to be more aware of it as he gets older. The look on his face when his aide guided him back into his chair was one of realization. He knew that he wasn’t doing what he should be doing. We see that look a lot…like he’s disappointing the world around him as much as he’s disappointing himself. He walks around apologizing all the time, and it breaks my heart.

I can’t imagine what that is like for him. Always being watched. Constantly being told that whatever you’re doing is something you shouldn’t be doing. And feeling like it’s out of your control.

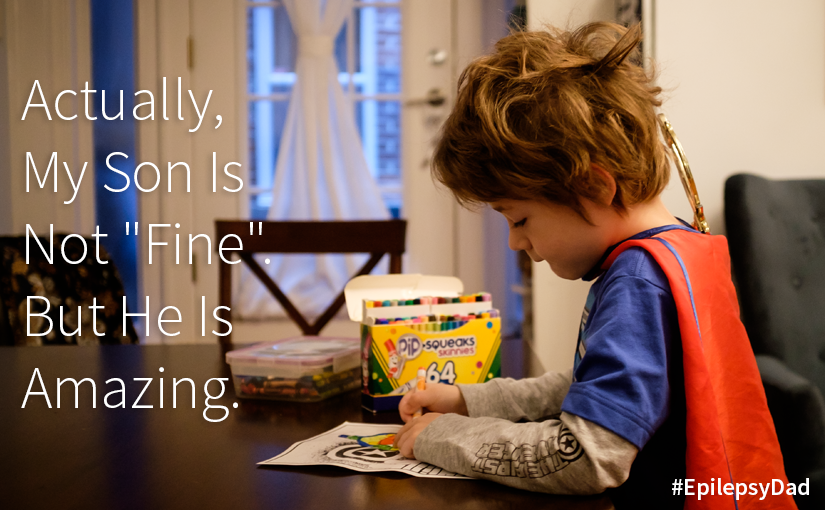

This isn’t one of those posts where I have an answer. We’re getting help for him and as a family to try to figure it out. We’re surrounding ourselves with people who will help him succeed. We are trying to help him build confidence and treat his condition as a condition and not a reflection of his value as a human being. We’re trying to boost his confidence and find ways to make him feel as special as he is. Having to do that for my son is hard and it makes me sad. It’s an uphill battle. But I would do it all day, every day, if that is what he needed.

Because there is nothing more important.