One day last week, after I dropped my son off at school, I walked past the playground and the late kids being hurried by their parents across the street. The kids were a few years older than my son and, on the walk home, I began to think of when I was their age and lived in an apartment complex in Connecticut.

I remember there was a common area between the apartments and the street that was covered in grass, with a big, green boulder that I used to climb, imaging it was the tallest mountain. My friends and I used to meet on the grass and play baseball, or tag, or ride our bikes on the sidewalk through the buildings.

My sister was among the older kids that used to also congregate by the boulder, usually either ignoring or taunting their younger siblings. But there were no parents. Many of our parents, including my mother, were single parents or low income parents trying to make ends meet, so they were working or inside catching up on chores and other duties. So we were left to go outside, and play together, and to fill up our days with whatever we felt like doing.

If the older kids got to be too much, my friends and I would grab our fishing poles and walk through the woods adjacent to the apartments to a small creek where we would catch frogs and small fish and where I swear I saw a river monster (which was probably actually something like a muskrat). There was a sledding hill on the other side of the complex, and patchy wooded areas that we could explore with plenty of trees to climb. Our ability to roam without parental supervision or babysitting by our older siblings made us feel very free.

We don’t have any spaces like that near our house, and living in a big city is a completely different environment than the area around those apartments when I was my son’s age, but I wondered if my son would ever get to experience that same sense of freedom that I had when I was living in those apartments. Even if there were places to roam and their weren’t busy streets to navigate, will his seizures prevent him from being able to run off and play without the watchful eye of my wife, me, or another caregiver? Will he always have to be around other people, particularly someone who knows what to do if he has a seizure?

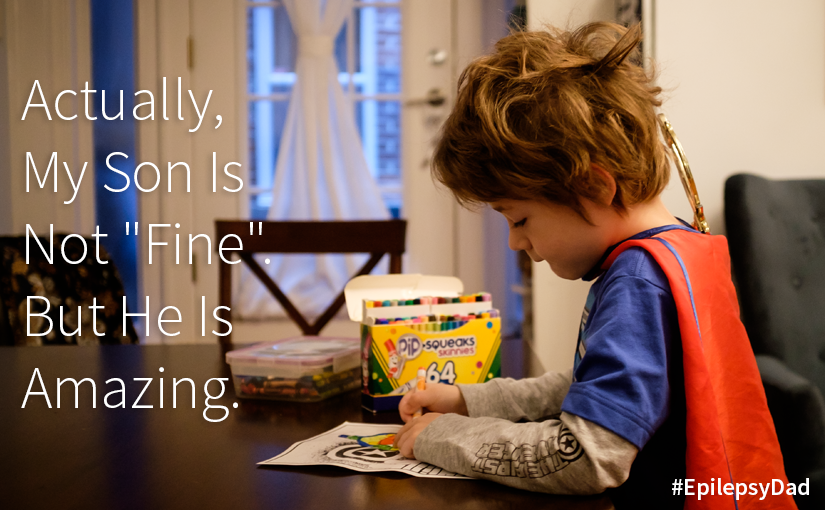

I’ve always said that I didn’t want epilepsy to make my son feel “less than”, or for it to keep him from doing anything he wants to. But the reality is that it might, especially if we continue to have such a hard time getting his seizures under control. He probably doesn’t notice it as much now, because he’s six and because he’s not supposed to venture out in to the world by himself. But as he gets older, and as he’s not able to experience the same freedom that his friends do, I’m going to need to find a way to make it okay.