This post is part of the Epilepsy Blog Relay™ which will run from March 1 through March 31. Follow along and add comments to posts that inspire you!

If you saw my son on the playground, you might not notice anything wrong with him. He’d be running, playing, and laughing alongside the other children. Epilepsy is a “hidden disability”. It can remain invisible, hiding its nature until a seizure reveals the cruel truth. For my son, his seizures occur in the early morning hours outside the view of the rest of the world. While there are traces of other symptoms of his condition, they, too, often go unnoticed. As a result, we control whether to expose his condition to the people around us.

There are times when it is easy to know that we should disclose his condition. At school, he is on a 504 plan so his epilepsy is well documented, and he has special accommodations during the day. His aide and his teacher have both come to understand him and are able to better adapt to his needs. While many of his classmates can’t grasp what they cannot see, we are as honest with them as we can be. It’s hard to not notice the aide, the breaks and the absences. Ignoring the reason for them would confuse his young class more.

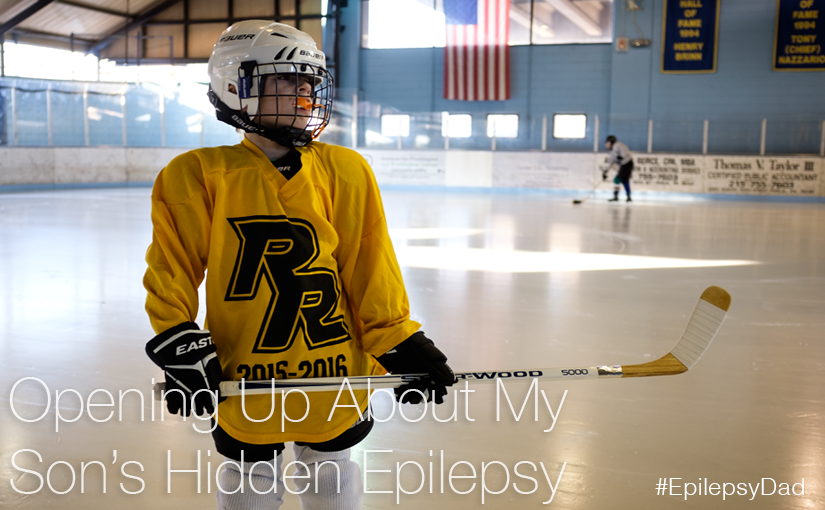

Sometimes disclosing his epilepsy is a matter of safety. Before we signed him up for hockey, we asked if they were comfortable with a student that had epilepsy. On the first day of practice, we talked to the coach to remind him. When my son had a seizure on the ice, the coach was prepared and we spoke with him afterward, as well. It would have been unfair and irresponsible to hide my son’s epilepsy, even if he hadn’t had that seizure. It also could have easily traumatized his coaches. It’s bad enough seeing a seizure when you know one is possible. It’s another thing to be caught off guard.

As his father, I worry what the stigma of epilepsy will do to my son. Classmates made him feel different because his ketogenic lunch was strange. They weren’t trying to be mean, but it caused my son to hide his lunch for weeks. As he gets older, the comments may not be as innocent. My wife and I work hard to give him a good foundation of strong values and a deep sense of self-worth. I don’t want him to feel shame because he has epilepsy. But he’s my little boy, and knowing that he’ll face challenges because of his condition is hard. The idea that he’ll be stigmatized by others because of it is unbearable. That alone makes me want to protect him and never tell anyone about his epilepsy.

So I hide his struggle (and ours) from those around us. I don’t talk about his condition or volunteer any information for fear of judgment or pity. To the parents from his school and his hockey class, he’s another normal kid. To the people passing on the street and the people that see him on the playground, he blends in with everyone else. Some days, those moments feel like a gift that I don’t want to let go of.

It’s tempting to take the same approach in every situation. But epilepsy is such a big part of his life that people won’t know the real him with that piece missing. They won’t know how hard he works to function on a bad seizure day or to navigate the fog caused by his medicine. They won’t know that he has different limitations and abilities. They’ll never understand him without that piece of the puzzle and I want him to be understood. He is worth understanding.

Is it better to feel like everyone else when you know that you aren’t? Or is it better to always feel different but to always be yourself? Should the answer I’d give for myself be the same that I’d give for my 7-year-old son? These are the questions that I found myself asking as I tried to wrap up this post for epilepsy awareness. I struggled for a long time trying to come up with a concise answer, but I couldn’t. Because there is no answer. There is just doing the best that I can with what I am capable of doing and with my son always first on my mind.

NEXT UP: Be sure to check out the next post tomorrow from Audra Sisak at www.hislifewithautism.com for more on epilepsy awareness. For the full schedule of bloggers visit livingwellwithepilepsy.com. And don’t miss your chance to connect with bloggers on the #LivingWellChat on March 31 at 7PM ET.