We sat in the exam room, waiting for the doctor.

It was his regular follow-up with his neurologist. She has managed his care for almost ten years. She has been with him through keto, multiple surgeries, and the rollercoaster of physical and emotional effects that his condition has had on my son.

This appointment, in particular, was one I had been dreading ever since my son brought up the topic of driving with his therapist. She suggested that he ask his neurologist about it at his next appointment.

This was that appointment.

There was a significant buildup between his first mention of driving and this appointment. I know it was on his mind, so it was on my mind, too. It wasn’t the anticipation of the question or the uncertainty of what the answer might be. The mounting pressure came from the finality of that answer when it was given.

The pressure built up slowly as the days went on. But the morning of the appointment, it spiked. Asking that question was the only thing on my son’s mind. He brought it up when we left the house. He brought it up when we got to the hospital. He brought it up to me when our appointment started, even before the pleasantries were done. I motioned for him to wait.

After his exam, his doctor asked if he had any questions.

I looked at my son and nodded, indicating it was time for his question.

He looked at the doctor and asked the seven-word phrase that he had been holding onto for weeks.

“Will I ever be able to drive?”

The pressure that had built up finally exploded, pushing the air out of the room.

I looked from my son to the doctor as she formulated her answer. I saw her shoulders lower as she took a breath. Careful, concerned, and compassionate. But also direct.

“Probably not,” she said. “No.”

I looked back at my son. I couldn’t judge his reaction. He sat there, taking a punch to the gut and not even flinching. He knew what the answer was going to be. And then he heard it. And then… nothing.

I knew what the answer was too, and it’s not like I was hoping for a different answer. I just hoped it wouldn’t hurt. I hoped it wouldn’t matter.

I finally took a breath. I wanted to just hold him. I wanted to find a positive spin. I wanted to not think about how his condition has taken so many things from him.

My heart was on the floor. I was gutted.

“I will always tell you the truth,” his doctor added.

The appointment ended soon after, but the weight of that moment stayed with me. I could see him turning it over quietly, the way he processes most big things. A few days later, I checked in with him to see how he was feeling.

“I’m ok,” he offered.

That is usually his first response to questions about his feelings. I gently pressed, trying not to project what I thought he must be feeling after hearing from his doctor.

We landed on disappointed and resigned. Having the answer helped quell the uncertainty, even if the answer wasn’t what he wanted.

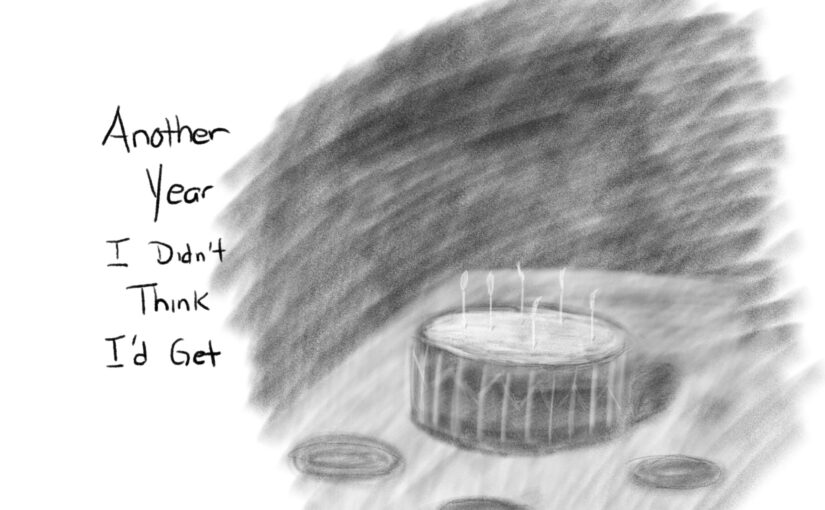

Moments like this remind me of something I live with every day: he faces losses most teenagers never even consider. They arrive quietly, in small conversations and clinical truths, and I know they won’t be the last. There will be more moments like this in his future, more things he has to let go of. But we will keep living our lives around what he can do, not just what he can’t.

And no matter what lies ahead, I’ll be right beside him.