We don’t really know how long our son was in status epilepticus.

We had moved to a new city only six months before, around the time when my son had his first seizure. He had his second a few months later, which lit a fuse inside his brain. We started to see more “ticks”. I didn’t think anything about them, at first, because they looked very different from the seizures we saw. But he started having more of them. The fuse was burning and it was quickly reaching the explosives.

In movies, when a hero defuses a bomb, it’s very dramatic. She’s on the radio with the experts who are talking her through the process.

“Take off the cover.”

Our hero unscrews the cover, exposing a spaghetti of wires. “Done,” she says. “I see the wires.”

“Now, “ a voice says through her earpiece, “carefully trace the wires back to their source. You should see a control board with a power source.”

Our hero uses the back of her hand to wipe the sweat from her brow. She squints her eyes as she uses the screwdriver to carefully push wires out of the way to reveal a circuit board with a series of glowing lights.

“Done. I see the board, ” she confirms.

“Ok, coming off the back of the board you should see a red wire and a blue wire. You need to cut the blue wire.”

Our here slowly grabs the wire cutters from her pocket. In her left hand, she uses the screwdriver to push back the wires further. As she starts to weave the wire cutters into position with her right hand, she stops.

In movies, when a hero defuses a bomb, there is a blue wire. In our story, there was no blue wire. The spark ignited. The bomb exploded.

Inside my son’s brain, an uncontrollable chain reaction began and sent electricity coursing through every cell. His body contorted. He was disoriented. He slept. The cycle repeated for days as another team of doctors tried to contain the secondary effects of detonation, like stopping the spread of radiation after Chernobyl.

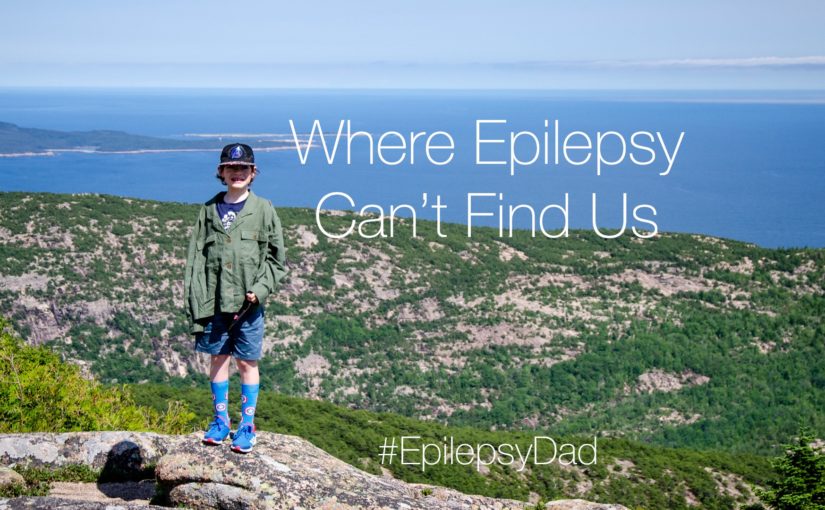

While the doctors managed to prevent the worst possible outcome, the damage was done both from the seizures and the tactics employed to put out the electrical storm. We’re still dealing with those consequences years later. But our son is here, and he’s happy, and we are grateful.