It’s great to have people in your life who want to help. I know how lucky I am to have friends and family who care, who check in, who ask what they can do. I am very fortunate.

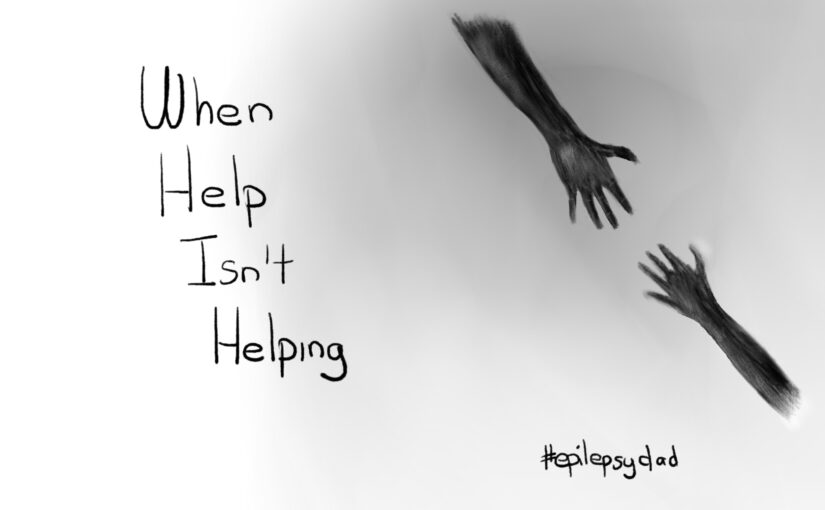

But when you’re already overwhelmed, even the offer of help can add to the weight. Suddenly, instead of just managing my own list, I’m trying to come up with something for someone else to do so they feel helpful, because they genuinely want to be helpful. And that becomes one more responsibility, one more set of feelings to consider.

The other day, my mom offered to help. I told her I’d let her know if something came up. She gently pushed back and said I needed to find something for her to do—some way for her to contribute—because she needed to feel like she was helping.

And in that moment, my stress level doubled. What was meant as support felt like another to-do. Another thing to figure out. Another emotional dynamic to manage. The offer wasn’t helping; it was giving me more to carry.

I know some of this is me. I’ve never been good at asking for or accepting help. Maybe it’s because I don’t want to put anyone out. Maybe it’s because I feel like I should be able to handle it on my own. Maybe it’s because I don’t always feel worthy of the help being offered. Or maybe it’s that the help being offered doesn’t match the help I need in that moment, and then I feel guilty for not having a task ready.

There are so many obstacles in my way—my sense of responsibility, my discomfort, my self-doubt. I don’t want people to think I’m ungrateful. I don’t want them to think I don’t need them. I don’t want them to stop offering.

And sometimes, the truth is that what helps isn’t a task at all. Sometimes it’s just knowing someone is thinking of us. Sometimes it’s an invitation to grab a coffee or play tennis or step away from everything for an hour. Sometimes the help is simply the reminder that we’re not doing this alone.

But so often, help doesn’t feel like help. It feels complicated.

Maybe that’s because I don’t yet have a healthy relationship with accepting help. Maybe there’s something I need to learn about receiving care instead of only giving it.

Because the reality is: my son will likely always need support. I want him to grow up knowing he can ask for help without shame. I want him to feel worthy of help. I want him to see that needing support doesn’t mean he’s a burden.

I want to model that for him.

But I’m still figuring out how to do that while shielding him from the stress and overwhelm that comes with being the one who needs help. I’m still learning how to receive help without turning it into another source of pressure.

Maybe the lesson starts with accepting that I can’t do everything alone. And maybe the next step is allowing others—genuinely, openly, imperfectly—to help lighten the load in the ways they can.

Even if that means learning how to let help actually help.