My son stepped out of the car and headed to the facility without waiting for us. The near-full moon lit his way from the parking lot to the bright light shining through the glass doors.

I jogged to catch up with him. I said what dads are supposed to say.

“Remember what you’ve learned.”

“Try your best.”

“Have fun.”

He nodded as I held the door open, and we stepped through the threshold and into baseball evaluations.

I scanned the waiting area while my son headed to the bench to prepare his gear. The kids were clustering in groups, classmates and previous teammates catching up on their year. There were a few familiar faces from last season, and we exchanged greetings. A few made a point to say hello to my son, too.

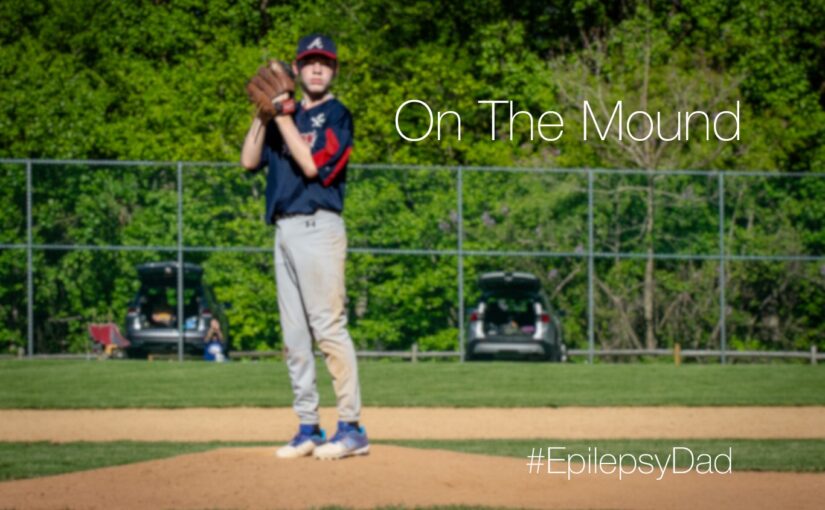

My attention shifted to the players on the field. The evaluations are comprised of fielding, throwing, and batting exercises. First, a coach hits about ten ground balls that the players field and throw across the turf to a mock first baseman. After fielding, they grab their batting gear and head into the cage to face ten pitches from a pitching machine.

For most of the players, these activities are routine. In fielding, the coaches try to hit difficult bouncing balls, but for the most part, the players catch the ball in their glove and rocket it across to the awaiting glove. A few kids had missteps but, for the most part, recovered in stride.

It was the same with batting, although the differences between the elite players and everyone else were more noticeable. The compact swing, the crack of the bat, and the speed at which the ball left the bat were impressive for most grownups, and these players were only fourteen.

I watched as my son walked over to check-in. He told the coach his name and stood near the netting, waiting for his turn. The other kids continued to chat and joke while my son stood alone. He tried to join a joke at one point, but it landed flat. I’m not sure he noticed, but it was all I could see.

We’ve noticed the drift between my son and his peers growing wider. At school, it’s less apparent because he’s surrounded by other children with similar intellectual, emotional, and social challenges. But in situations outside that bubble, there’s a spotlight on those differences.

When it was his turn to step onto the field, I gave him a smile and a thumbs-up.

Even during the brief warmup, I could see how tense he was. His feet weren’t moving, and it looked like he was doing the drills he does with the off-season coach we hired rather than casually warming up with the other children. After every throw, he’d look our way…I’m not sure if it was for approval or comfort. But it was making me anxious with worry, so I continued to smile and overexaggerated a deep breath that I hoped would encourage him to relax.

His fielding started off slowly, and his throws were off. A few went wide, while others bounced short but were on target and made it to the coach’s glove. Still, he stuck with it, resetting himself after every throw to receive the next ball.

After fielding, he grabbed his helmet and bat and stepped into the cage. The balls were faster than he had seen in a while, but he made contact with a few and then started to struggle. I heard the coach who operated the machine encourage him and, after he made contact with one, told him that was a good swing to end on.

When he stepped off the field, I could he see the disappointment on his face.

“I didn’t do as well as I could have,” he said with his head down.

My heart sank. The conversation with his coach last year about the skill bar getting higher every year came back to me. We had no aspirations of our son being a professional player. Still, baseball was one sport he’s been able to play all through his health struggles, partly because of the nature of the game itself but also because we’ve been very lucky with the coaches we’ve had that supported him and made him feel part of the team. Compared to where we had been with his challenges, every catch, every hit, and every smile was one we never thought we’d see. The idea that we’re close to losing that was hard to process. I did my best to keep those thoughts from appearing on my face.

We spent the short car ride home trying to understand his feelings, which is often difficult. My son doesn’t always know or have the words, which occasionally leads to him agreeing with whatever feelings we ask about, so we’re never quite sure if they are his feelings or our projections.

By the next morning, he was feeling a little better. I don’t know if it was because of our talk or because he forgot how it made him feel. Either way, I was grateful.

I felt a little better, too. It’s easy to get stuck on what he can’t do or what is taken away. The losses seem so much bigger than the gains, even though there are many more gains than losses. That he was able to play baseball at all was such a gift, one that we enjoyed for many years. If and when the time comes when he isn’t able to do it, either because he can’t keep up or because he doesn’t enjoy it, we’ll try to be grateful for what we had and find that next thing that brings him joy.

A few days after the evaluations, we’re not there yet. My son seems ready for the season. We’ll keep our fingers crossed for another kind coach and supportive team and look forward to the experience ahead.

Play ball.