My grandfather was one of the most influential people in my life. He passed away when I was only 18, although we didn’t see each other as often after I moved away with my parents 5 years prior.

I didn’t have enough time with him.

He worked at a Pratt & Whitney factory. I was fascinated by the aircraft his engines powered into the sky, and every year, he would bring me a company calendar highlighting them. I would hang the calendar on my wall, marvel at the specifications, and build models of the aircraft to show him.

My sister, cousin, and I would spend a lot of time at my grandparents’ house, especially over the summers. We’d play in the yard he kept groomed with his riding lawnmower, which he would sometimes let me drive. We’d climb the apple trees overlooking the garden he had made for my grandmother. And I’d rest in the cool basement with him, watching golf on the old television until we both fell asleep.

There were times when he worked the night shift, and when we spent the night, we’d watch him go to work after dinner and come home in time to have breakfast with us. Despite his inconsistent schedule, I remember him consistently making time for us.

He instilled in me the importance of hard work and education, and he’s part of the reason I continued to get my bachelor’s and master’s degrees even after I had already started my career without them.

I’ve been thinking about him because my dad passed away recently, and it made me think about the relationship my son had with his grandfather.

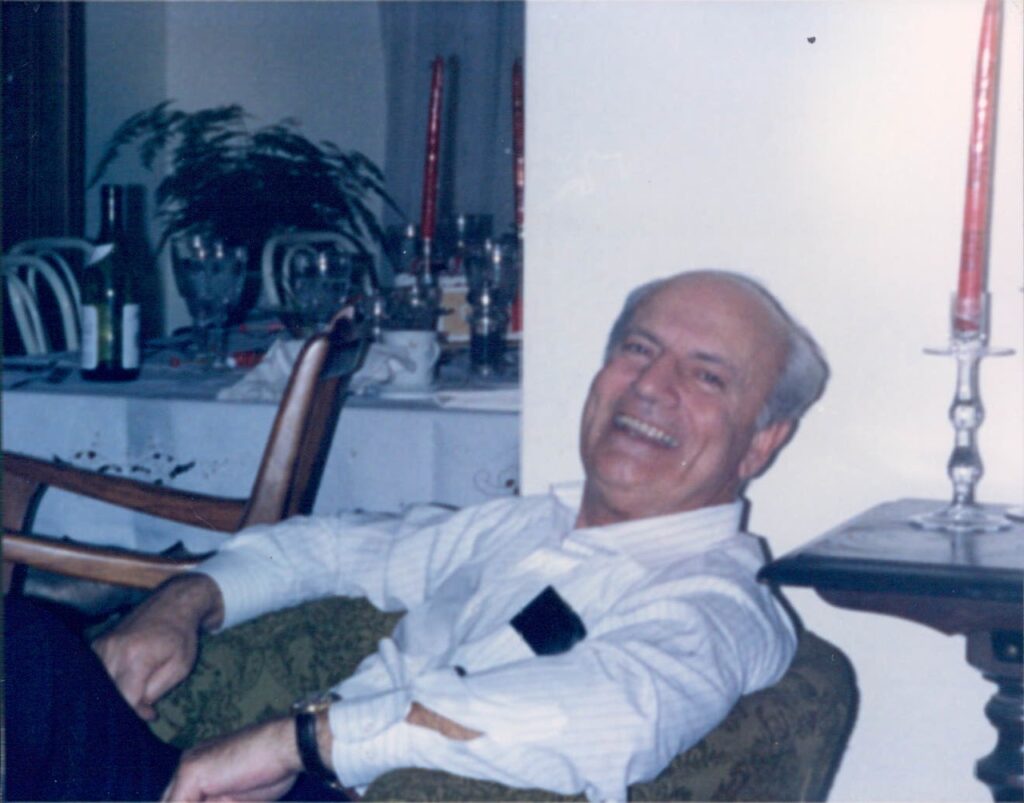

Growing up, my dad (technically my stepdad, who I called “dad” as soon as he married my mother when I was 11) wasn’t especially warm. He was kind, and he was smart. I learned how to fix bicycles and do basic home repair and electrical work because he invited me to help him on projects around the house. But there was always an emotional distance. There were few hugs and no “I love you.” But he was a good dad and provided a good life for us.

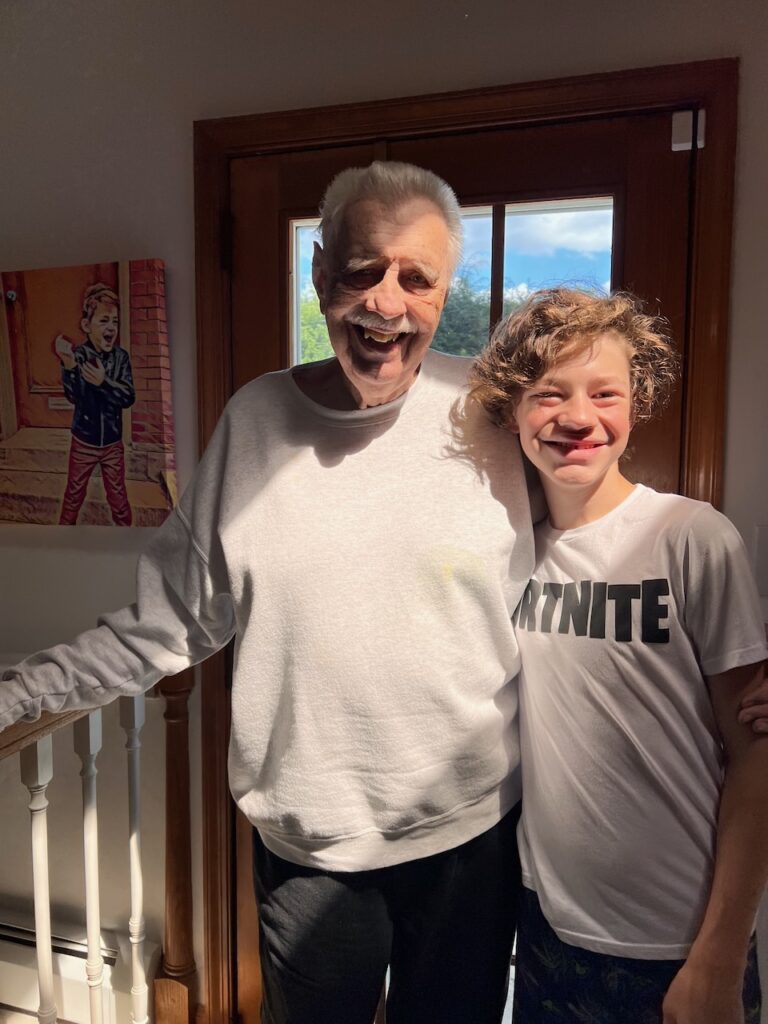

When my son was born, that started to change. We would visit my parents in Florida a few times a year, and my dad was always genuinely happy to see my son. He would greet us at the airport and welcome a big hug from his grandson. We would stay at their house and spend time together. I have pictures of my dad watching my son jump and splash in the pool and also following my son along a jelly bean trail left by the Easter Bunny. My dad was thrilled with every present and card my son gave him, as if each was the best gift he had ever received and was exactly what he wanted.

As my son got older and after he was diagnosed with epilepsy, I could see my dad opening up. My son’s challenges cracked open a piece of my dad that even he didn’t know was there. He would always tell me how well my son was doing, how amazed he was at what my son could do, and how much he wanted my son to be okay.

We moved my parents to live near us a few years ago. By then, my dad’s health had started to decline, both physically and mentally. But he maintained the same excitement to see us and his grandson every time we visited. We would have holiday dinners together, and while it was different from when I would go to my grandparents when I was young, it was a time for my son to spend time with his grandparents, too.

Even though it got more challenging for him to get around, we took my dad to a few of my son’s baseball games. I’m not sure he always knew which player was his grandson, but he was so happy to be there and always told my son how proud of him he was. When I would stop by after work, the conversation with my dad would always turn to asking how my son was doing and how big he was getting.

“He’s not a kid anymore,“ my father would say. “He’s a grown man.”

Somewhere along the way, my father started to say “I love you” to us. At first, it was in response to us saying it to him. But then, he started to offer it himself.

I don’t remember my grandfather saying “I love you.” We weren’t a big “I love you” family, so I thought it was normal. He would tell me he was proud of me and other, safer, phrases, so I didn’t know what I was missing.

That’s one of the changes we made as parents. My wife brought that into the family, and I am grateful she did. I tell my son that I love him at school drop-off, randomly throughout the day, and every night before he goes to bed. It was nice to extend it to my parents so that my son could also receive it from them.

The last time my son saw his grandfather, he and I had stopped by to visit. My dad looked old and tired and had fallen asleep, slumped to the side in his recliner. At one point, he woke up, saw us, and smiled. He asked about baseball and commented on how tall my son had gotten.

A week later, I sat in the same room. My dad was on a bed provided by hospice instead of his usual recliner, and he was in a deep sleep. I talked to him about the memories he helped create and how grateful I was. I spoke to him about his grandson and how well he was doing.

That would be the last time I would speak to my dad.

A few days later, he was gone.

Loss has a way of making us reflect on what truly matters. For me, it’s the time we have, the love we show, and the memories we leave behind.

I am grateful that my son got to have time with his grandfather, especially these last few years. He got to see a man who, over time, learned to express love in ways he hadn’t before. He got to hear his grandfather’s pride, feel his warmth, and know, without question, that he was deeply loved.

And now, he’ll carry those memories with him, just as I carry my father’s and my grandfather’s with me. In that way, love never really leaves us—it simply finds new ways to be passed on.