A few weeks ago, before school started, my son was invited to a play date with other kids that were going to his new school. It was a good opportunity for us to meet the parents and for our son to meet his future classmates, and he was excited, even though he was having more seizures in the days prior. The day of the play date, he took a nap, woke up, and had another big seizure as he was getting dressed. With eyes full of tears, he said that he didn’t want to go anymore. I sat down on the floor next to him, held him and rubbed his back, and I asked him why. “Was it because of the seizure?” Initially, he said yes, but then he said that it was because he was nervous.

I let him know that it was okay to feel nervous, and that everyone gets nervous. I told him we didn’t have to go, or we could go and leave if the playground became too overwhelming. He cried for another minute, then he took a deep breath, put on a very stern face, and said out loud “I can do it.” He stood up and finished getting dressed. I checked in with him a few more times as we packed up his stroller, giving him probably too many opportunities to change his mind, but he was committed and we headed down the street to the park.

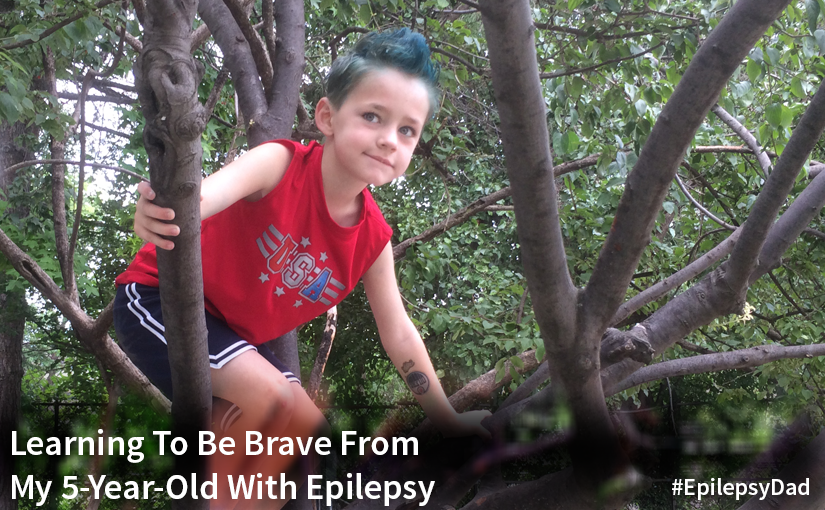

When we got to the park, he stayed by my wife and I initially, but he introduced himself to the other children. Eventually, one of them led him over to a tree that they were climbing, and my son eagerly joined in. He would climb the tree, maneuver to a branch, and drop down, Ninja Warrior-style.

On one of his climbs, he had a seizure. I saw his body stiffen and heard the tell-tale sound that accompanies his seizures, so I grabbed him and gently lowered him to the ground.

Once the seizure stopped, my mind started to race. Did the other kids see? Would they cast him aside? He wet his pants during the seizure. Did the other kids see that? Would they make fun of him? I questioned whether we should have brought him to the park at all and why I convinced him to put himself out in front of these new people when I knew he was already having a bad seizure week.

As he started to regain his composure, I asked my son if he was alright, and if he wanted to go home. “No,” he said. “I want to stay.” After a few more minutes, he stood back up. We dusted him off and did an inspection. His pants weren’t that wet and, aside from being a little hazy, we couldn’t see anything wrong. I asked what he wanted to do, thinking that running away and going home was the best option. “Climb the tree,” he said, as he walked back over to the tree. He grabbed a think branch with both hands, put his foot on the trunk, and pulled himself up.

I was never very brave, and I struggle to not project my fear on my son. I want so desperately to not poison his bravery with my overbearing desire to protect him from the world. I was different as a kid. I was awkward, and uncomfortable, and afraid. I know what it is like to be picked on for being different. The world can be a cruel place when you are different.

My son has epilepsy. He has seizures. That makes him different, too. There will be times where those differences are on full display, in front of his friends and his peers. I don’t want him to feel shame for who he is or because he has epilepsy, so my natural tendency is to hide. But he is teaching me that the right answer isn’t for me to encourage him to run away when he has a seizure or when he falls down. It’s my job as his dad to encourage him to put himself out there, even on those days when it’s hard. It’s my job to encourage him to get back in to that tree and climb.