A few weeks ago, we went to a birthday party for one of my son’s friends. It was a small gathering, done safely. We didn’t know the other family there, but they were very friendly, and the kids all got along.

Near the end of the party, we gathered together and sang “Happy Birthday.” After the birthday boy blew out the candles, the other children eagerly reached for a cupcake. My son, however, was sitting off in the corner. I walked over to him. “Hey pal, you ok?” I asked, knowing what the answer would be.

“I don’t feel included.” The words came from his mouth and punched me in the heart. It had been so long since we attended a birthday party that I forgot to make my son a keto-friendly cupcake.

I sat on the bench next to him and put my arm around him. “I’m sorry, ” I said. “I forgot.”

I told him I would make it up to him and that I would make him a cupcake as soon as we got home. But I knew it wasn’t the same thing. He’d be eating that cupcake at home, all alone, instead of surrounded by his friends, participating in what they were doing, being just like them. Right now, he wasn’t included. He was on the outside.

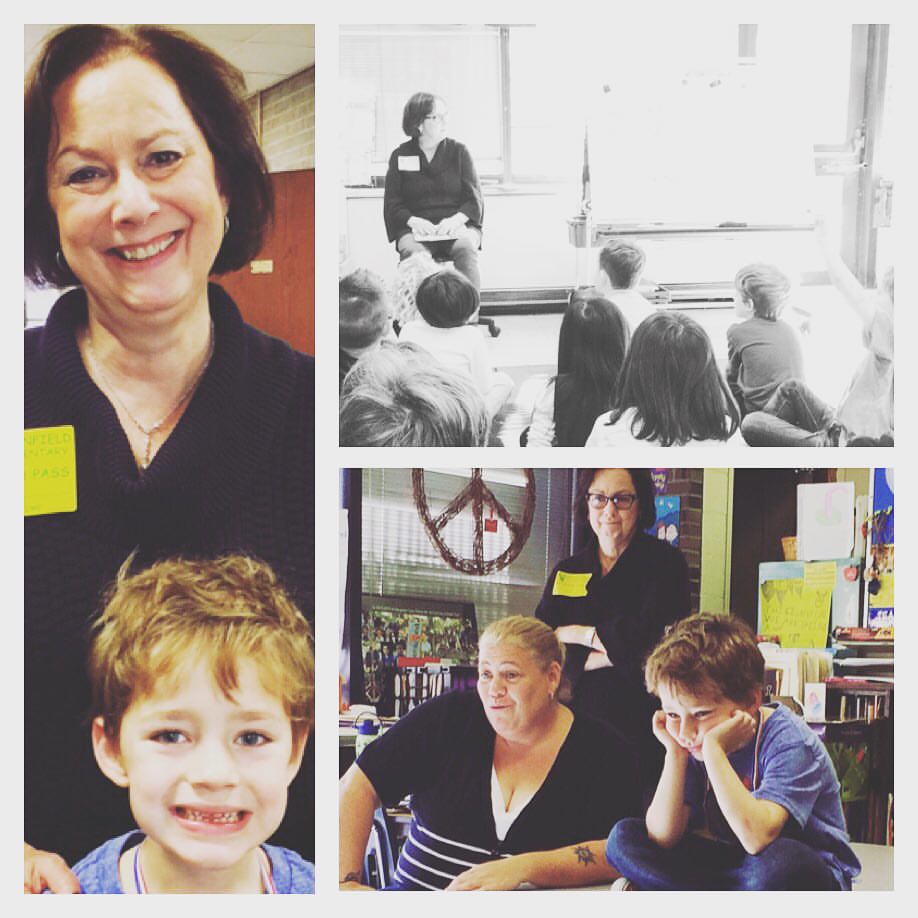

He’s been on the ketogenic diet for so long, and he started so young that it seems like it has always been this way. I take for granted that he’s always had a different meal than us. But, as he gets older, he’s noticing more how that makes him different. At his new school, the other kids have sandwiches and bags of chips for lunch. He brings keto ice cream and a few chips. They have cookies for dessert. He has cheese or macadamia nuts. When they have special events or cooking, he has to eat the substitute we send in. He never gets the same.

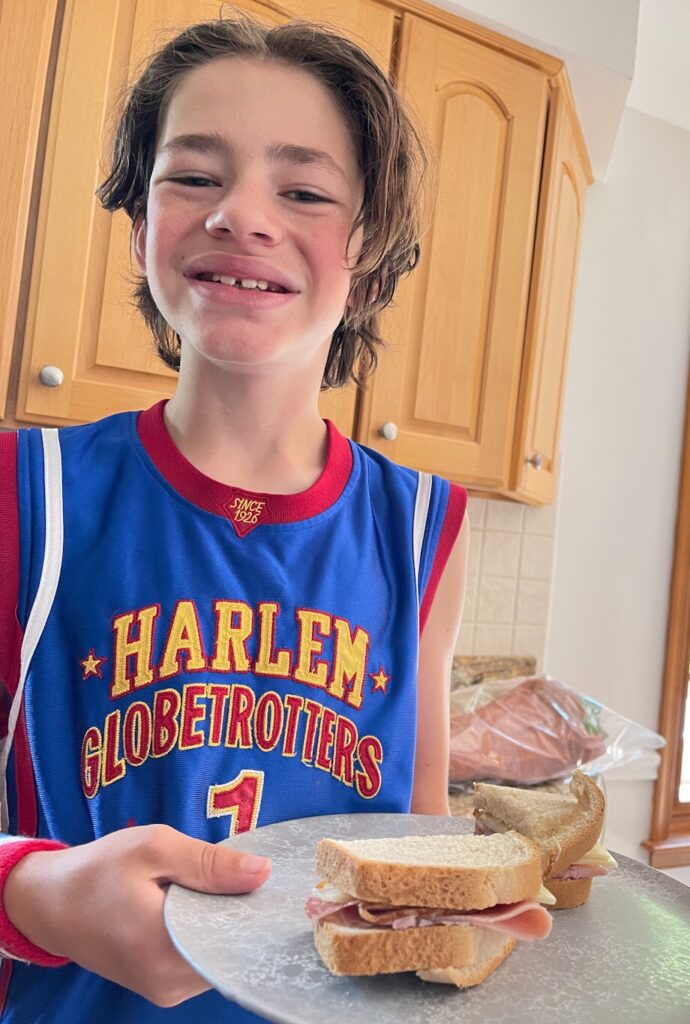

Change is on the horizon, though. After more than seven years on keto, we’re moving to a modified Atkins diet, opening a new world of food for him. The other day, we found a low-carb bread and made sandwiches for lunch. As we sat at the table, I smiled and watched him close his eyes and take a big bite out of the middle of his sandwhich. He chewed for a few seconds, then opened his eyes and looked at me, smiling. “I can have sandwiches for lunch at school, ” he said. “Just like everyone else.”