This week, my wife and I are meeting with my son’s school to update his 504 plan. A 504 plan is intended to ensure that a child with a disability has access to learning and receives accommodations to help them succeed academically. In my son’s case, his plan outlines breaks, seating placement, a shortened school day, and special assistance for attention and behavioral issues. The plan is put together collectively by the parents, nurse, teacher, and school district with input from my son’s medical team and support services and it is meant to be a “living document” that will change as my son’s condition or capabilities change.

This is our first year with a 504 plan. Even though we’re only a few months into the school year, we are pulling the team together to make adjustments. Some changes are good, such as lengthening his day since his endurance has improved. We also have a better sense of how he handles the day, so instead of basing his breaks strictly on a time, we can place them after harder tasks so that he can spend more time in the classroom with his peers. But we also need to address some issues that many parents of children with epilepsy face when trying to get the right services for their child.

Looks Can Be Deceiving

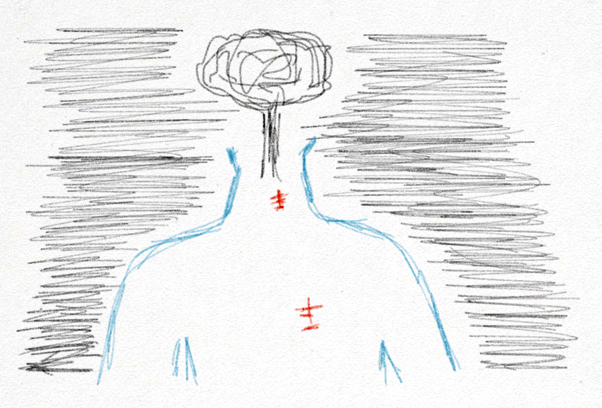

Most of the time, if you look at my son, he looks like a normal, healthy kid. I am extremely grateful for that, but it makes requesting services for him difficult because he doesn’t look “look sick”. Epilepsy is included in the class of conditions called “invisible disabilities”. While a seizure itself might be external, many of the effects surrounding epilepsy are internal. Fatigue, depression, and problems with attention and cognition are just some of the issues that my son deals with every day. On the outside, he might look like a normal 7-year-old boy and it’s easy to want to treat him that way. Too many times my son doesn’t get a break that he needs because he “looks fine” but, by the end of the day, he’s so physically exhausted that, not only is he not actually learning anything, he has more seizures that night and the next morning that cause him to start the next day already exhausted. It’s only after

Epilepsy is included in the class of conditions called “invisible disabilities”. While a seizure itself might be external, many of the effects surrounding epilepsy are internal. Fatigue, depression, and problems with attention and cognition are just some of the issues that my son deals with every day. On the outside, he might look like a normal 7-year-old boy and it’s easy to want to treat him that way. Too many times my son doesn’t get a break that he needs because he “looks fine” but, by the end of the day, he’s so physically exhausted that, not only is he not actually learning anything, he has more seizures that night and the next morning that cause him to start the next day already exhausted. It’s only after a few days following seizure-filled nights that my son physically fits the “sick kid” profile.

Not All Epilepsy Is The Same

Epilepsy covers a broad range of seizure disorders. A teacher mentioned that she had a student with epilepsy that would have a seizure, sleep at her desk, then wake up and be fine. When she described that experience, she did so in a “don’t worry, I clearly know epilepsy so I’ve got this” tone that raised the “you don’t got this” alarm bells in my head.

Epilepsy is more than just seizures and there are an infinite number of variables surrounding the seizures that make each case unique. My son rarely has seizures during the day, but depending on how tired he is, he may have more at night and in the early morning hours, which affects how rested he is going into the next day which perpetuates the problem. The state of his brain at any given moment dictates his behavior and his ability to retain and recall information. His head is constantly swimming in medication and the side effects of those medicines are exacerbated depending on his cognitive load, seizure burden, and his physical condition. So not only are not all cases of epilepsy the same, but people with epilepsy can show a wide range of symptoms and effects on any given day.

Not Everything That Looks Like “Normal Behavior” Is

“All kids his age…” Anytime someone starts a sentence with that phrase, I know that I’m going to have to break out the soapbox. First, “all kids” don’t do the same thing. But most importantly, the behavior that looks like the “normal” attention problems of a first grader are actual misfirings of the neurons in my son’s brain that are preventing him from recalling any information. The glassy eyes and the “no one is home” look could be the result of a seizure or the way that his medicine is affecting him today so his extra-slurred speech and his frustration trying to piece together a complete thought are not normal development problems, either, especially when they vary throughout the day.

Even with the best intentions, treating something as “normal” has both the risk of setting my son up to feel like a failure because he can’t control what is happening to him and prevents the identification of what is actually causing the behavior and the ability to address that cause.

Things You Can Do

We are very new to this world, but we are extremely grateful to have a wonderful support network around us and to have had many people go before us and share their lessons. To continue on in that spirit, here are a few of the lessons that I have learned that may help you navigate this long, difficult road.

Have The Conversation

Balancing my desire to have the world treat him as a “normal” kid and making him feel like a normal kid with the reality that he has special needs is a challenge I face every day. Not everyone else does or has a reference for what that means. Having a dialog with the teachers and the school district and talking about their perceptions is an important piece of having everyone on the same page. “It’s great that you have seen a seizure, but here is how my son is different from that other student.” As the teachers have more interactions with my son, and as we continue to talk about what they have seen and what things we are seeing at home, we’ll all have a better picture and be able to adjust the plan to better suit my son’s needs as they continue to change.

Have The Information

My wife and I have talked leading into this meeting about what is working with his current plan and what isn’t working. We’ve talked about what things we need to bring up, how to bring them up, and what documentation we need to provide to support our position, and we will have that documentation available. Doctor’s reports, neuropsychological tests, reports from wraparound services. Perceptions are hard to change but the best way to support the request for services that your child needs is with data.

Have A Support Network

One of the best resources that we have available to us is our support network. Other parents that work tirelessly to navigate the system, social services through the hospital and the state, and epilepsy groups such as the Epilepsy Foundation of Eastern Pennsylvania that have programs to bring epilepsy education into the classroom. This network provides the guidance and information we need to ensure that we are asking the right questions and asking for the right services for our son. In some cases, we’ve brought people from this network into these meetings. In the end, we have built a team that we can leverage to do what is best for my son.

Have The Courage To Fight

If you’re averse to conflict like I am, get over it. It may seem like the system is set up to oppose these special services. They cost money, they disrupt the normal flow and structure of the school day, and especially with an “invisible disease”, the system may try to convince you that your child doesn’t need these services. As we’ve been told many times, there is no one that will be a bigger advocate for our son than us. Be that voice. Partner when you can. Fight when you must.

Additional Information

There is a lot of good information about what to ask for in a 504 plan, and I wanted to share these links that I found useful. If you have other suggestions or resources to share to help other parents going through this process, please share them in the comments.

http://www.greatschools.org/gk/articles/section-504-2/

Sample 504 plan for epilepsy: http://www.epilepsynorcal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Sample_504.pdf

NEXT UP: Be sure to check out the next post tomorrow from Eisai/Sean at livingwellwithepilepsy.com for more on epilepsy awareness. For the full schedule of bloggers visit livingwellwithepilepsy.com. And don’t miss your chance to connect with bloggers on the #LivingWellChat on November 30 at 7PM ET.