My son does this thing where the muscles in his face loosen. His cheeks look chubbier as they drape softly down to his jaw. His mouth separates a little, and I can see the tip of his tongue pushing through. Sometimes he’ll swallow slowly, which at the same time seems automatic but also like it takes all of his concentration and energy.

That is one of the signs we see that lets us know when he is tapped.

There are other signs, too. He has an even harder time with his executive functioning and memory than he normally does. It’s more difficult for him to regulate his emotions. He gets angry and frustrated. But that look on his face is the look of someone who has given everything they can for the day. It’s how we know he’s done.

This isn’t something that only happens occasionally.

It happens every day.

There are days when it happens sooner, usually around this point of the school year or when we did such things after a baseball game. There are days when it happens later, like on a lazy weekend. And there are days when it happens more than once, usually once before and then later on after a nap. But it always happens. Every day. Every day, my son gives everything to get through the day.

Every day, my son gets tapped.

The other day, I sat on the edge of the bed with my son and studied his face as he leaned against his pillow, watching his iPad. I tried to be present with him. I asked him what it felt like and if there was anything I could do for him, but even asking a question forces him to try to muster enough energy to think and respond. He’s such a good kid that, even tapped, he tried to find enough energy to process my question and think of an answer. It felt cruel. I felt terrible. And so I didn’t ask any more questions, and I sat with him and rubbed his head and let him tune out.

Unless you knew him, you wouldn’t know that anything was going on. He might just look like a tired kid. Its invisible nature is one of the many curses of epilepsy. His doctors, who have seen the same in other patients as they see in my son, understand it. But it’s harder to convey to others because they don’t know him and because they don’t have a reference for that level of exhaustion.

“Imagine climbing a mountain. Now, imagine if everything you did felt like climbing a mountain. Now, imagine if that is what you felt like every day. “

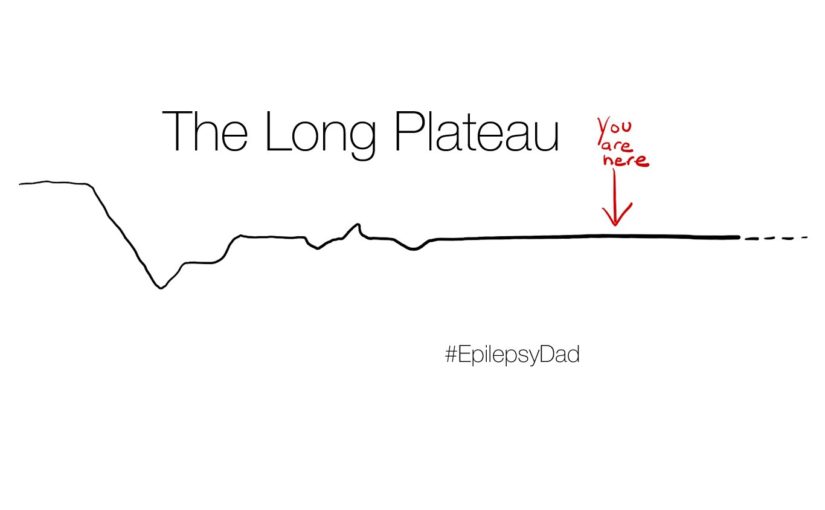

Every day, my son climbs that mountain. Every night, he falls asleep only to find himself back at the base of the mountain when he wakes up. Then he starts to climb again. He pushes, he grinds, he stumbles, he gives everything he can until his body, and his brain can’t do anymore.

Every. Day.

He’s eleven years old.