We were coming off a good weekend. We celebrated my wife’s birthday on Saturday, and we ended Memorial Day visiting friends, having a swim lesson, and staying up a little later to see part of the first game of the hockey finals. We put my son to bed tired but happy.

Just after midnight, the first seizure came. I heard the sound come from my son’s room a second or two before the sound came through the speaker of his monitor. By the time I got to him, it had passed. He was sitting up in his bed disoriented, so I helped him lay back down and waited for him to fall back to sleep.

The next seizure came a few hours later. The next one an hour after that. And the next one an hour after that. It was like aftershocks after an earthquake, except each of them was just as intense as the one before it. He had at least four that I saw, but we learned during the overnight EEGs that we don’t see them all.

When he does anything that exerts an effort mentally or physically, a nap-time seizure or a collection of seizures during the night is likely to follow. We bowled for an hour and he had a seizure during his nap. After a morning baseball game, a seizure. Even though he only goes to school for a few hours, he’ll often have a seizure during his nap.

We tried to explain it to his school. It’s not just about what he can handle in the moment. The exertion carries beyond the activity itself. It show’s up as more seizures, which set him up to be more tired the next day. That lowers his seizure threshold for the next day, too, making him more likely to have seizures or requiring him to spend more energy regulating his emotions or attention. It’s downward spiral that ends with the husk of a boy too tired to function.

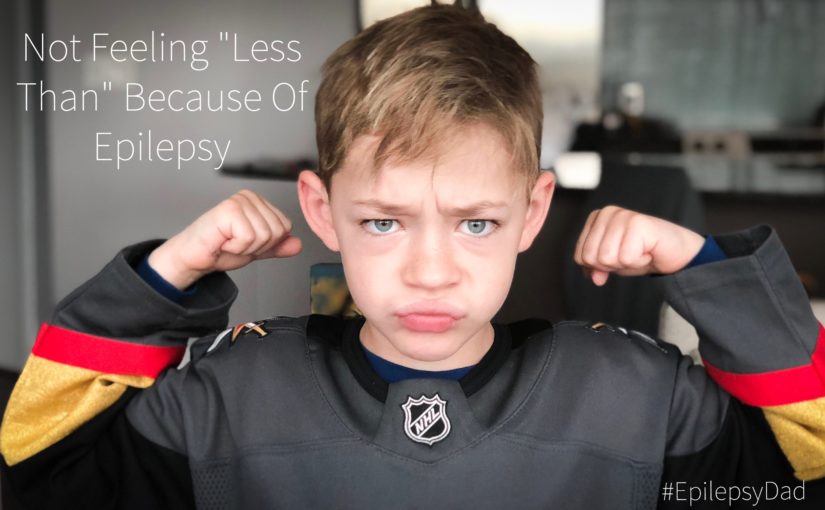

It feels like the universe collects a toll from my son based on how much he gets to actually live his life. It imposes a penalty to knock him back down and remind him of his limitations when he tries to exceed them. Someone with uncontrolled seizures shouldn’t play baseball. Seizures. Someone with uncontrolled seizures shouldn’t be progressing in school. Seizures. Someone with uncontrolled seizures shouldn’t be going to the skate park, or an amusement park, or a hockey game. Seizures.

Every time it happens, I question whether we did too much. But I gave up wondering if we should be doing anything at all, because that’s having no life. That’s letting epilepsy win. That’s not giving my son the life and the world that he deserves. So we’re careful and we’re calculated in deciding what to do and how much to do. We do our best to protect our son but let him be part of the world. We introduce as much downtime as possible so that we can distrupt his pattern of exhaustion and let him do the things he loves.

The universe seems committed to collecting its toll, but we’re doing everything we can to minimize how much my son has to pay. Because we’re going to keep on living.