I thought we were going to be a hockey family. I grew up watching the Hartford Whalers and would pretend to play hockey on the frozen ponds when I was a child. When I moved back to Florida after my military service, the Whalers were no more, so I latched on to the Tampa Bay Lightning and started taking hockey classes at a nearby rink. When I moved to Colorado, I joined a recreational team and played for years until the late nights became too much, and I settled for playing the occasional drop-in game.

My son and I started playing floor hockey as soon as he could walk. He was on the ice taking skating lessons when he was two, and by the time he was four, he started hockey clinics. When we would go to a hockey game, my son would make me keep my phone handy in case the Colorado Avalanche needed him. It was awesome.

Around that time, we moved to Philadelphia. By then, my son had had his first seizure, but it was only one, so we still looked for ice rinks in the area for him to continue skating. But, by that winter, things had taken a turn for the worse, and he would wind up being in and out of the hospital for the next few months.

By the spring, we were out of the hospital, but his seizures were still not under control. We were in a new city with no friends, no family, and the only support we had was at the hospital. We had just spent months isolated in the hospital and wanted to give him something to do. Skating wasn’t an option, at least until he became more stable, but we found a tee-ball league nearby and signed him up.

That first season was rough. There were wonderful moments watching him play with the other kids as he learned to hit and throw and play the game. But there were constant reminders that we hadn’t yet figured out what was wrong. We would watch as my son stood on third base and slumped over because of a seizure, only to pop back up and try to get back into the game. Sometimes he could; other times, we’d rest and hold him on the sideline as his tiny body recovered, watching the other kids continue to play. It was heartbreaking. But he loved being on the field, so we made it work.

Eventually, and after he stabilized a bit more, we signed him up for some skating lessons and a hockey clinic. They taxed his body and brain, and we had at least one seizure on the ice, but he was happy. Again, though, his seizures and the side effects of his medication took over, and skating was too much for him. For a while, we tried working on hockey skills on a concrete rink, but even that was too much. We still loved going to games and playing on the tennis courts in the park. My son still dreamed of a career in the NHL, but skating and being on the ice took too much out of him to be able to do it consistently.

Baseball, though, was different. Each spring, we would sign up, even though we didn’t know how much our son would be able to handle. Each spring, I would fill out the signup forms and list his condition and make notes to warn his coaches about his issues with stamina and attention. Each season, my son would show up on the field and work hard to be a part of the team.

Through the years, we were lucky with the teams he was on and especially the coaches. The experience the coaches created for him was exactly what he needed, and it gave him a bit of normalcy during a very unstable time. And the coaches were good people, too. One year, his coaches attended our local Epilepsy Foundation gala, donating their time and money to a cause so important to our son and family.

When the pandemic hit, we missed those moments. When the weather permitted, we would go to a field as a family and play. As fun as that was, it wasn’t the same. Just as the world was beginning to open up and we were going to register for the upcoming season, we uprooted and moved out of the city and missed the registration for our new community, and missed out on another season.

This spring, though, we signed him up as soon as registration opened. Again, I filled out the forms and felt nervous filling out the “Medical Conditions” section. I was worried that we had found a bubble of support in our previous league where the coaches knew my son and that this new league wouldn’t be as positive. He’d be surrounded by entitled suburban kids and parents who have known each other for years. I was worried he wouldn’t fit it because it’s easier to do when everyone is new, but here he would be the only new kid coming in, and it had been years since the last time he played. I was worried that this experience would take away something that he loved to do.

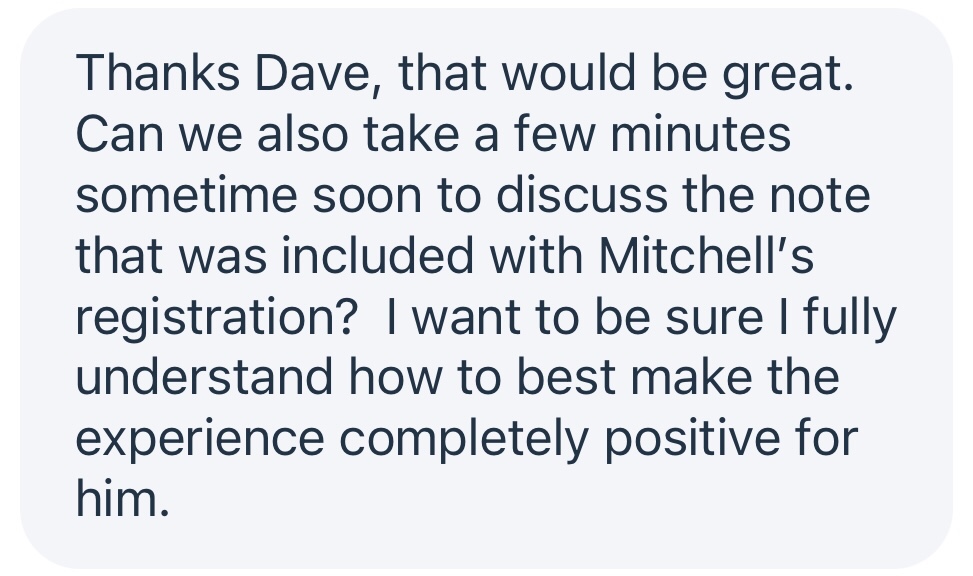

I suppose it could have gone that way. But shortly before the season started, I receive this message from his coach:

Immediately, I felt better. That simple gesture lifted the worry and fear I had been carrying from the time I signed him up. The conversation that followed was sincere and kind and set my son up to have a positive experience on the team. We continued to communicate as we figured out where my son was physically and what he was capable of (which turned out, as always, to be much more than I assume he is).

Even though many of the other kids had been playing together for years, my son felt like a part of the team. The players celebrated hits, and solid fielding plays. They cheered for each other and got to know each other…Fortnite was a popular topic and something that my son had in common. A few kids from our neighborhood were on different teams, so my son also developed connections across the league. I couldn’t help but smile as I saw the kids chat and mingle during batting practice before a game, like professional baseball players getting ready to hit the field.

A highlight for me was during a day of celebration that the league puts together for the kids that raises money to support the organization. One of the events was a Home Run Derby for the 12-year-olds who would be “graduating” from their division. Only a few kids could hit the ball over the fence, but there was a point system for hitting deep balls that allowed everyone to participate.

My son was excited to participate, always believing he could hit a “dinger.” Nervously, I signed up to pitch to him during the event. Selfishly, I thought it would be a good father/son moment. But, even though I’ve been pitching to him since he first picked up a bat, I wanted to ensure that he was set up for success. When I asked him what he preferred, he said that he wanted me to pitch, so I practiced for days ahead of the event.

When I was out there on the mound, it wasn’t about whether or not my son hit any home runs (he didn’t) or how far he hit the ball (very, very far). It was watching him step up to the plate and do something brave. It was watching him take that deep breath, set himself up, and swing the bat. It was watching the smile on his face or the way he holds the pose at the end of his swing when he makes solid contact. It was hearing the other players in the dugout cheering for him when he sent a ball to the outfield or to try to reassure him when he had a string of infield hits. It was, after his time ended, walking up to him and telling him how proud of him I was and seeing how proud of himself he was.

The season’s final game was a “Graduation Game,” where they put all the 12-year-olds on teams one last time. It felt like an All Star Game where all the kids who had gotten to know each other over the season could go out and play one last time. After the game, each player received a plaque commemorating the season. They called up each player one by one while the others cheered. My heart swelled when it was my son’s turn, and I hid behind my phone to not embarrass him with my huge smile and watering eyes.

I am so grateful that my son has found something that brings him joy. There were times when I only focused on the loss of hockey…the idea that something he loved was taken away from him by his condition. There were times watching him have seizures on the field or struggle with his stamina and attention that I worried that he wouldn’t be able to find anything else. There were times when my overprotective, helicopter-parent nature and the terrifying experiences we’ve had with epilepsy have caused me to focus on the things he shouldn’t or can’t do.

But going through these experiences and watching my son continue to surprise me with what he can do…it’s humbling and wonderful and inspiring. It has caused me to move from a place of fear to a place of hope and gratitude. It has caused me to stop worrying as much about creating a perfect experience and to appreciate and enjoy the experiences as they come more fully. Every day my son teaches me something just by being himself. Every day, I feel like the luckiest dad in the universe.