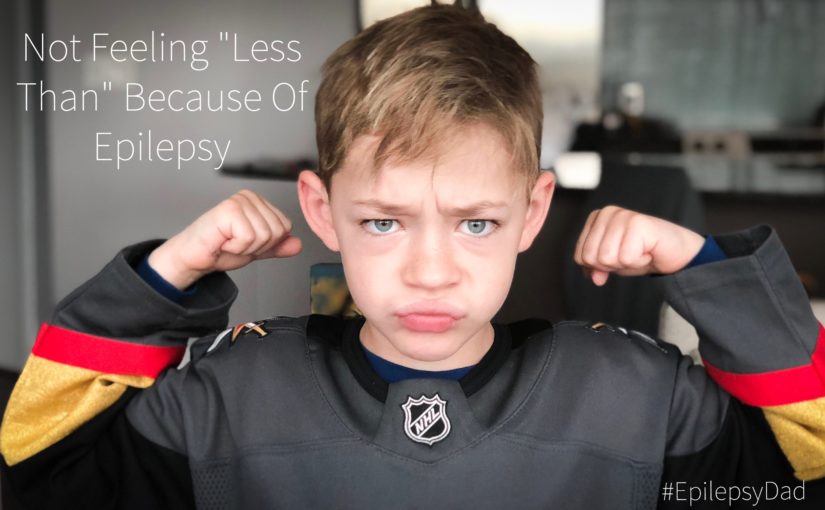

One of my fears for my son is that the world will make him feel “less than” because of his epilepsy.

There is a quote by Temple Grandin where she says “I am different, not less,” referring to her autism. I like the sentiment of her message. Having a condition like autism (or epilepsy) doesn’t make one less of a human being or less important than anyone else. But “different” doesn’t go far enough to describe the impact that epilepsy has on my son. “Different” is blonde versus brunette, hazel eyes versus brown eyes. Those differences are superficial. Epilepsy affects every aspect of his life, from his behavior, to how tired he gets, to the food that he eats, to how he learns and how he feels about himself. Having epilepsy is more than about being different. It’s a vital part of understanding my son.

I struggle with balancing the importance that epilepsy has on his life with just saying that it makes him “different.” I want to hide his condition to protect him from the people who will use it as ammunition to attack his sense of worth. At the same time, I want to share that part of him with the world so that it can see how special he is. But I know I can’t have it both ways. I know that the tightrope between protecting him and showing the world who he is will get harder to walk as he gets older. The more he shares that part of himself, the more vulnerable he will be to the people around him that don’t understand or who are looking to exploit his condition as a way to boost their own perceived worth. At eight, the jabs are more innocent. At sixteen, the jabs will be meant to injure.

So what is the answer? Maybe my son will grow out of his epilepsy and never have to deal with feeling different when he is older. It could happen, but I’m not betting on it. Even if it did happen, though, that’s not the answer. I need to continue to build him up, to help him understand his value, to understand that his epilepsy does make him different but that it does not make him “less than” someone who doesn’t have epilepsy. I need to continue to reinforce that message until he accepts it for what it is…truth. It might not feel like the world’s truth, but it must be his.