A few weeks ago, I took my son to the airport. It was the first time he was going on a trip without me. And not just without me, he was traveling for the first time as an unaccompanied minor.

He was growing increasingly nervous leading up to his trip, and each day, his anxiety showed more on his face. I woke him up early that morning to give us plenty of time to check in and get my gate pass, which added a slow, sleepy haze to his nervousness.

We passed through security and headed towards the gate. I checked his boarding pass and looked at the signage. We were two terminals away and the gate was the second to last in the terminal, which meant we had a hike in front of us.

I led the way as he trailed behind me, his loaded backpack hanging over his shoulder, adding weight to his burden. I offered to carry it for him, but he declined. His face was blank, his mouth slightly open, drawing in air, as we pushed forward until we entered the terminal for his gate.

“I’m so hungry,” he moaned.

“Ok, pal, we’ll find something closer to the gate.”

We pressed on through a largely empty terminal, the stores and eateries closed. He reminded me every few minutes of how tired and hungry he was, in case I forgot. I said a little prayer that there would be a place for him to get food and that he would have enough time to get it near his gate. Fortunately, there was a food court with a Sbarro within view of the gate.

He slumped into a chair, dropping his bag off his shoulder, as I went to order him food. I glanced over, and he had the same exhausted, blank expression on his face. I brought him a slice of pepperoni pizza and a glass of water, placing them in front of him.

After it cooled, he hunched over and took a few bites.

“I’m too tired to eat.”

“Ok, pal.”

I packed up his food and picked up his backpack.

“Let’s get you to the gate,” I offered.

He stood up slowly and followed me the rest of the way.

His flight was already boarding, so I went to the desk to let them know he was there. We stood off to the side as they finished boarding, which is when there was enough of a pause for me to start missing him, even before he left my sight.

I thought about the previous day. When I dropped him off to school, he asked me if I would play basketball after I picked him up.

“Maybe,” I said. I knew I had a big day at work ahead of me, and I didn’t want to commit and then disappoint him if I was too busy or tired.

And I was. But the first thing he said to me when he stepped into the car was to ask about playing basketball. Every exhausted fiber of me wanted to say ‘no,’ but I knew I’d miss him terribly and wanted to spend every minute with him.

“Only if you want to lose,” I responded. The smile on his face, followed by him cracking his knuckles and neck, was everything, followed closely by our time on the court playing, and laughing, and being together.

Standing at the gate, I reminded him of our games the day before, including the game where he beat me 21 to 0. There was a glimpse of energy, and a smile, and I felt lighter.

The agent finished boarding the other passengers and came to us to escort my son to the plane. I gave my son a hug and a kiss, put on a brave smile as he disappeared down the jetway.

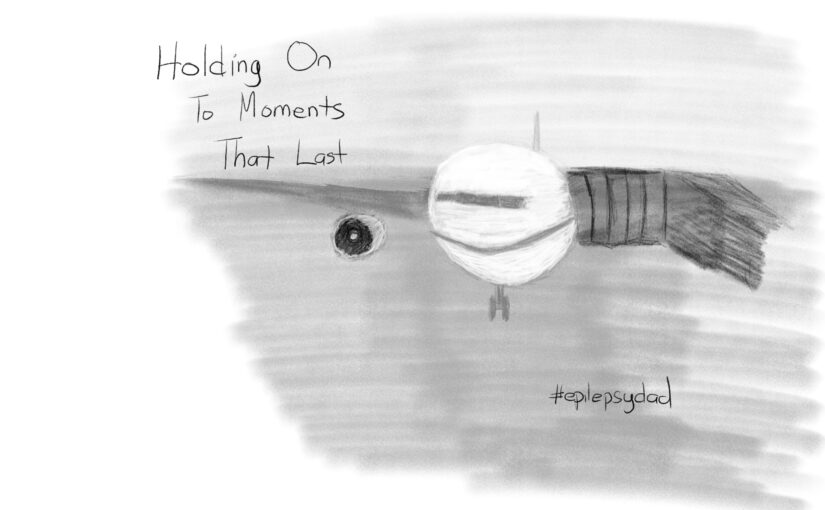

I stood at the window, watching the pilots finish their preflight checks before the jet bridge was retracted. The airplane pushed back and entered the flow of traffic to taxi to the runway. Once it disappeared from my view, I began my long journey back through the airport, to the car, and finally to the house, which felt emptier without my son.

It was terribly quiet.

But as I left later that morning to go to work, I saw the basketball on the floor of the garage and was instantly reconnected with my son through the memory of our games the day before.

He’s growing up so quickly. Each step he takes towards independence means there will be fewer moments like the ones we’ve shared. Each year, he’ll need me a little less, and that’s how it’s supposed to be.

But until then, I’ll seize every chance to create more memories, so that even when we’re apart, it feels like we’re still together.