Earlier this year, we bought a stroller for our 5-year-old son. After his condition deteriorated in the hospital, he came home with very little physical or mental stamina. Every exhaustive mental activity drained him, and ever labored step sapped his energy. Since we live in the city, getting anywhere involves walking, so we found ourselves isolated in our apartment. With no social interaction, no friends, and no sunshine, our confinement raised the tension in an already strained situation, which was not good for our family or for his recovery. The stroller gave us a way of getting out of the house without having to carry him so that we could rejoin the world outside.

Our son is tall and weighs 45 pounds, so we bought the biggest, most durable stroller we could find. Even so, he barely fits inside with a small bend of the knees and his head is a bit taller than the top of the canopy, but he is comfortable and the stroller lets us get to where we need to go without completely exhausting him.

One day, we headed across town to the market. As we turned up a street, I saw a woman sitting on a bench on the sidewalk. She was looking at us as we approached. It’s the city, so of course I know not to make eye contact. But as we passed, she pointed to the stroller and blurted out “Why is that boy in a stroller? Is there something wrong with him?”

We didn’t respond and continued past her as she raised her voice. My son didn’t hear her, or he didn’t understand what she was asking. Her question didn’t sound curious. It came across as accusatory, a reaction to seeing a big kid being pushed around in a stroller that was almost too small for him. It was the tone that is used to admonish a parent that is spoiling their child, not one of compassion for a difficult situation or even an innocent inquiry in to a situation that she didn’t understand.

I read a related story a few weeks ago about the family of a disabled girl having a note left on their car for parking in the handicapped spot because “they didn’t look handicapped”. The girl actually has a brittle bone condition, invisible to anyone that doesn’t know her story, hidden on the inside, behind a curtain of skin.

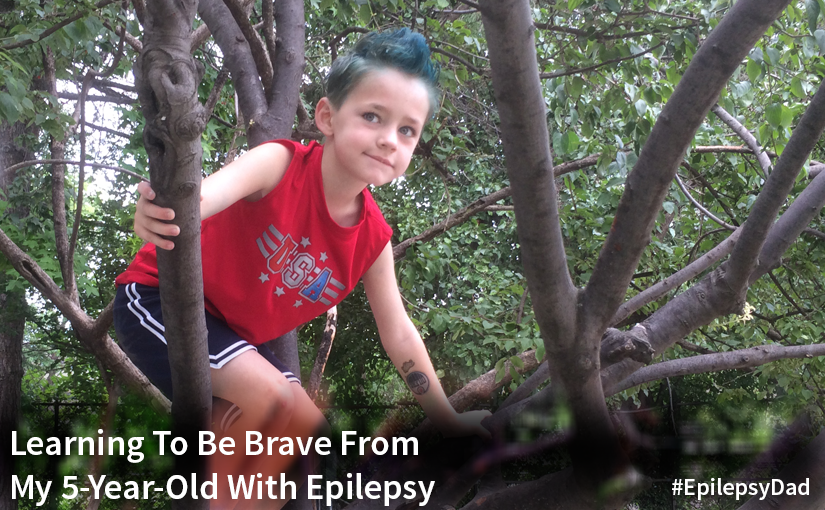

My son doesn’t look disabled, either. Unless you know him, you might not notice his drooping eyes that reveal his exhaustion. You might not know that his exhaustion comes from seizing all night long or that, in an unforgiving cycle, the exhaustion also leads to an increase in seizures. You might not see his behavior or psychological issues that come from an uncontrollable seizure cluster or the side effect of a medicine that he is taking to keep his seizures just barely on the side of control. You wouldn’t know about the nights that he has been so overtired that it took us hours to calm him down so that he would sleep. You wouldn’t know that the dark circles under our eyes are from the endless watching of the baby monitor and waking on every sound that comes from his room.

As I was writing this post, I shared it with my wife. I was struggling to find its meaning and the lesson that I hoped to share. In response, she posed a number of questions. Do I wish people wouldn’t judge my son for what they cannot see? Do I wish my son would learn to accept this judgement and not let it bother him? Do I want my son to learn from their mistakes and not do the same to other people?

Of course, I want all those things. I want my son to not be made to feel different, even though he is. I want him to understand that the world is filled with ignorant and callous people who will judge him for being different, and I want for their comments to bounce off him, even though I know that they will always hurt.

I want him to remember what it feels like to be made to feel different by people who don’t know him or his situation. Even if he can’t change the people around him, he can remember that feeling and can choose to be a person that leads with compassion instead of an ignorant judgement.

I’m just as guilty of rushing to judgement as the woman on the street. I make assumptions and use my own biases lunging in to situations without stopping to consider the entire story. Maybe the person that is angry on the other side of the phone just lost a loved one or is having a problem at home. Maybe the dad that snapped at his kid isn’t a bad father but is frustrated with something going on at work or is trying to deal with behavior issues stemming from side effects of an epilepsy medication. Having gone through those situations, I know how much a little empathy would have meant to me. Maybe the lesson is that if my son can lead with compassion and understanding, then so can I.

On second thought, maybe the lesson is that if he is going to do it, then so should I.