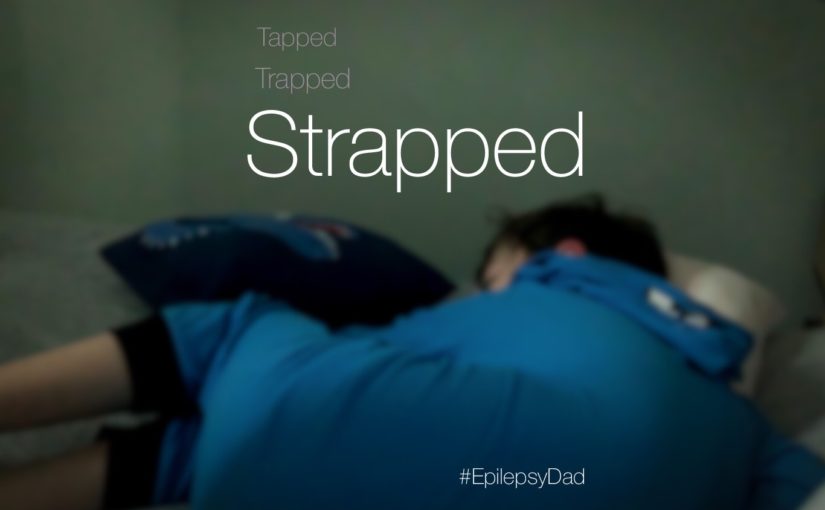

Tapped.

Trapped.

Strapped.

We toured another school the other day. Between the brick-and-mortar school that failed to accommodate my son and the virtual school that seems to be trying but may not be able to accommodate him, it’s becoming more apparent that the Industrial Era education complex is not for children like my son.

The school we toured is about an hour away. That’s a long drive to contemplate making twice a day, five times a week. We’re already strapped for time with counseling and therapies and appointments and jobs and life. But if this school can accommodate our son in a way that helps him learn, grow, and feel successful, then we will figure it out.

The school is a private school. It costs as much as a house payment every month to attend. Although I am extremely grateful for my job and the salary and benefits it brings, we are still a one-income family. We have insurance through my job and, in Pennsylvania, secondary insurance for my son, but they don’t cover everything.

We’re also trying to save up for when we’re gone. We want to do what we can to set up our son for a comfortable life because we don’t know what the future holds. He may be self-sufficient, or he may need help, and we don’t want him to have to struggle.

And we’re trying to do these things and make these choices while also living our lives. We like to get out of the city. We like to go on vacation and give our son and our family experiences that help make everything not just a chore. These things all cost money, and there is never enough money to do them all comfortably.

Of course, that’s when we have enough energy to do those things. Energy is another resource that is in tight supply. It takes so much of it to get through the day-to-day, juggling everyday responsibilities in addition to those of having a child with special needs. One reason we liked escaping to Maine last year was that it helped replenish our tanks, but those reserves quickly get depleted when we return to normal life.

Time. Money. Energy. Every day involves making choices between them to hopefully provide the best life for our son and our family. But it feels like the longer we have to choose between them, the more strapped we get for each.