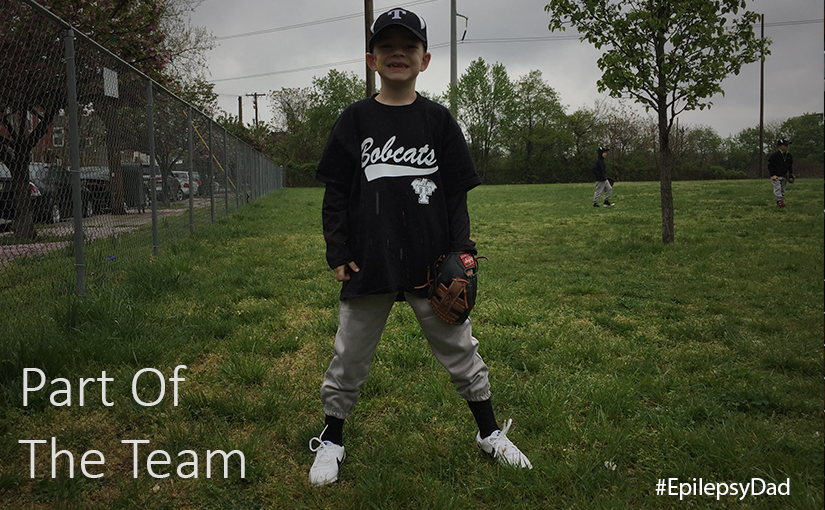

Spring is here, which means it’s time to hang up the skates and grab the bat and glove. This year, my son moved up from teeball, which I coached last year, to baseball. Since I’m not coaching this year, it meant having another conversation about epilepsy.

I still get nervous introducing people to my son’s condition. I try to strike the right balance between “he has a serious medical condition” and “everything is going to be fine.” It’s hard. Too much information can overwhelm even the most altruistic volunteer. But I’m not doing my job unless I am honest about all the potential challenges.

There are times when I wish that I could not say anything. I could hope for the best and let my son take part in an activity without a caveat. After all, he’s not likely to seize. And there are plenty of kids on the team that have a hard time listening or focusing. He could blend in.

That would be easier. The coaches wouldn’t have to be scared. I wouldn’t have to worry about him being treated differently. I wouldn’t have to face the reality of our situation. I wouldn’t have to make epilepsy a part of everything that we do.

But, the fact is, it is a part of everything we do. And it’s my job as a parent to do what is best for my son. I want to keep him safe but I also want him to enjoy the experience. The only way to do that is to have an open communication channel with the people in his life. We were told early on that we, the doctors, nurses, teachers, aides, babysitters…we are all a part of my son’s team. And like any good team, everyone needs to be informed so they can play their part.

When we talked to his coaches, they thanked us for telling them, then they asked what they could do to help. That night, they reached out to us again to let us know that they were happy he was on the team. To the father of a child with epilepsy, the best way to show that they were part of our team was to make him a part of theirs. They had done that with one phone call, and they continue to do it at every practice.

As anxious as I get about doing it, the more we have the conversation, the better we get at it. The better we get at it, the better people respond to it. And the better people respond to it, the less anxious I will hopefully be the next time. Which is good. Because it’s a conversation that isn’t going away.