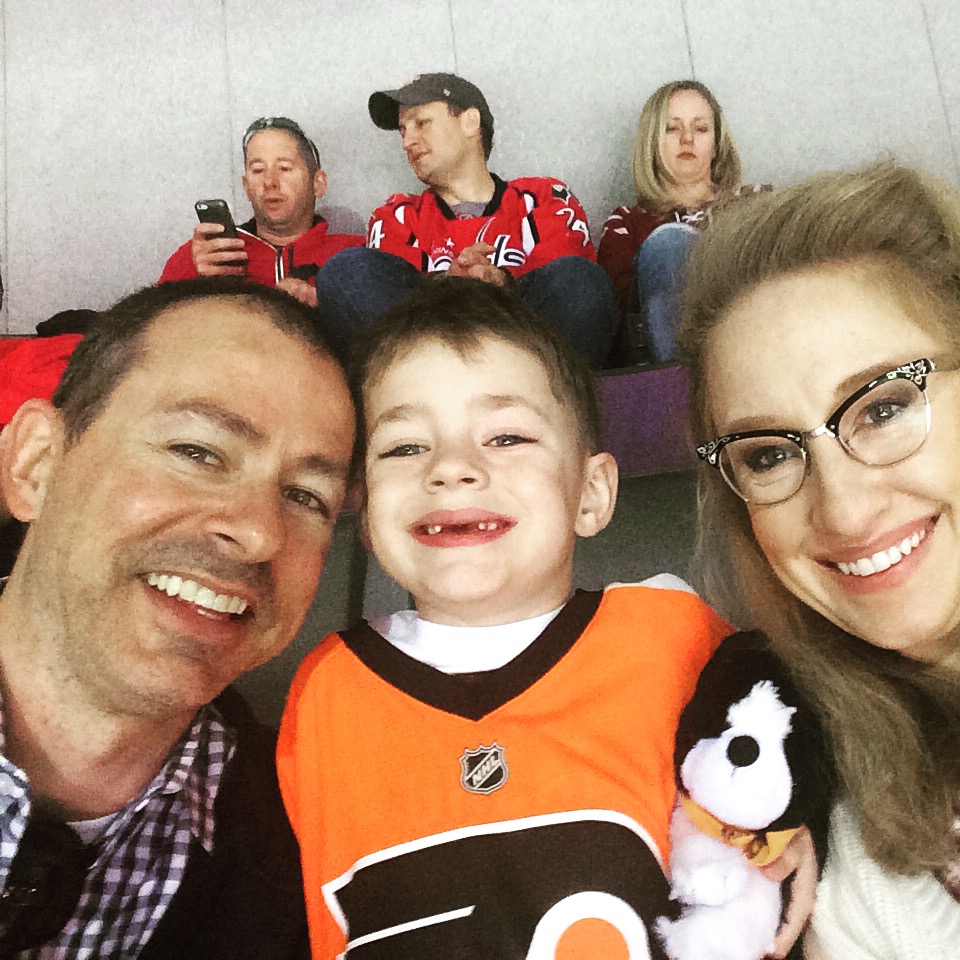

To the outside world, we look like an average urban family. I’m the aging dad, high (I’m still not calling it “receding”) hairline, close-cropped hair wearing city-chic because my wife dresses me. My wife, beautiful, hip with her too-cool-for-school (I realize no one says that anymore) sunglasses strutting down the sidewalk. And my son, wearing a Captain America helmet and catching air off the uneven sidewalk on his scooter.

We stop at our local market to pick up ingredients for dinner, because that is how normal, city-people shop. The shop keeper greet us with a friendly, welcoming smile and we exchange pleasantries that show that we’re local and are recognized as such. We stroll through the park to play catch and we see Jafar, the musician, and Mike, the juggler, whose names we know because we are locals. We pass them with a wave and they smile back with a hint of recognition.

There are two groups of people in our lives, those that are outside the circle and those that are inside the circle. Most of the world exists outside the circle, and they do not see the impact that epilepsy has on our lives or the complexities that we struggle with every day. When we buy those groceries, the shop keeper doesn’t know that the ingredients are only for my wife and I because my has epilepsy and is on a special diet. The other park goers don’t know that we are there only for a short time or for the first time in days because my son has enough energy to play that day.

For someone who writes a blog about being the father of a child with epilepsy, it may seem strange that I struggle with who to let inside the circle. As public as this blog is, it is still difficult to talk about what is happening with the people in our lives. How can I explain the heartache of helplessly watching my son have a seizure at the breakfast table? How do talk about why he keeps missing school? Or why he can’t do certain things or why we have to decline birthday parties and events that happen in the afternoon because he needs a nap?

Those outside the circle can never truly know us or our son because my son’s epilepsy is such a big part of our every day. Maybe I am worried about people judging him or judging us. I don’t understand how or why this is happening, maybe I’m so worried that they won’t understand that can’t let them in. It’s hard to overcome those fears, and to be open to sharing that piece of ourselves. It’s hard to trust other people, to be vulnerable, and to take that risk.

I am finding, though, that the more willing I am to take that risk and to share a glimpse of that part of who we are, the bigger that our inner circle becomes. His teeball team ask about him at every game that he misses. People at my office, friends and acquaintances that have met my son and seen him struggle react with kindness. They ask about him and pass along their well wishes. They donate when the call goes out for a charity event. This terrible condition that burdens my son and weighs heaving on our family has also revealed the gifts that come from having more people inside the circle that care.